Michelle Lavery on the Science of Animal Welfare

Contents

Michelle Lavery is a Program Associate with Open Philanthropy’s Farm Animal Welfare team, with a focus on the science and study of animal behaviour & welfare.

In this episode we talk about:

- How do scientists study animal emotions in the first place? How is a “science” of animal emotion even feasible?

- When is it useful to anthropomorphise animals to understand them?

- How can you study the preferences of animals? How can you measure the “strength” of preferences?

- How do farmed animal welfare advocates relate to animal welfare science? Are their perceptions fair?

- How can listeners get involved with the study of animal emotions?

Resources

-

Where to find Michelle

-

‘How do we know what emotions animals feel?’ by Alla Katsnelson

-

The Science of Animal Welfare by Marian Stamp Dawkins

-

More Twitter accounts to follow

Transcript

Note that this transcript is machine-generated, by a model which is typically accurate but sometimes hallucinates entire sentences. Also this time it thought Luca and Fin were one person! Please check with the original audio before using this transcript to quote our guest.

Intro

Luca / Fin

Hi, you’re listening to Hear This Idea. In this episode, I speak to Michelle Lavery, who is a program associate for farm animal welfare at Open Philanthropy and focuses on the science and study of animal behavior and welfare. Michelle has a PhD from the University of Guelph, where she focused on aquatic ecology and the lives of fish. I’m excited to get to be doing another episode on farm animal welfare. Looking at our back catalogue, I think that the last interview that Fin and I did exclusively on this course area was our mini-series all the way back in 2021. Improving the lives of farmed animals is just a really important and neglected topic, so it is great getting to learn and talk about it again. I’m also especially excited to get to talk to Michelle about this topic, who focuses on a unique part of the field, understanding what environments can make for happier animals. One reason is that this topic just raises deep scientific questions. What are emotions? How can we study them in beings that can’t directly communicate to us? When is it okay to anthropomorphise and when not? As Michelle explains, animal welfare science has made some interesting discoveries, but it is also still a very young and nascent field with a lot of work left to do. Another reason I’m excited for this topic is that it just seems impactful in a way that I’d previously not thought much about. Whilst many people might intuitively feel that many farmed animal practices are deeply horrible, like the cutting and battery cages, Michelle emphasises that it’s still critical to collect rigorous and impartial scientific evidence on these. Getting companies to change their practices, either directly or via policy, still often relies on being able to make a strong cost-benefit argument. So having evidence as to what these costs and benefits are can be really useful, and Michelle walks us through some recent examples of how these studies have been used. There is so much more important animal advocacy work to learn about, far more than Phil and I can cover in our show. Thus, if you find this episode particularly interesting, I strongly suggest you check out the podcast, How I Learned to Love Shrimp. It is hosted by Amy Odene and James Ozden, and they’ve had some great episodes so far, ranging from talking to the former president of the Humane League, to the current work being done in Africa, to wild animal suffering. Hear This Idea was privileged to help them set up earlier this year, which is to say that if you like our show, you’ll probably like theirs too. and Open Philanthropy.

Michelle Lavery

I’m Michelle Lavery, and I’m an animal welfare scientist working with Open Philanthropy’s farmed animal welfare team on trying to fund good, useful scientific research and technology development that improves animal welfare.

Luca / Fin

Awesome. And is there any question in particular that you’re currently stuck on?

Michelle Lavery

I mean, there’s a few. The kind of big overarching one that I think informs a lot of my thought process lately about prioritizing things is… kind of how you trade off the duration of a painful thing versus the intensity of that pain. So for like the question of, would you rather have like a low level annoying pain for your entire life or one day of absolute excruciating nonsense? And I think that’s like the various versions of that question, as you vary the duration and intensity of those two situations, becomes harder and harder to kind of trade off intuitively, and in a way that you know would generalize, because I think people have different experiences, people have different priorities, people have different pain tolerances we know, and so even within humans that’s a really hard question to resolve. And then understanding that in animals becomes even more difficult because it is really difficult to imagine these additional layers on top of that question, like whether you understand that the pain will end. whether you feel that you have some control over that pain. So is that low level annoying pain something you could take a painkiller for? Does the animal know that it can do that? So those types of things are things that I’m currently kind of working through thought-wise. And I don’t think I’ll come to an answer, but it’s, yeah, it’s just, it’s a constant. where I have a conversation.

Luca / Fin

Yeah, no, that sounds incredibly thorny and not the kind of question to do in a one-week research sprint.

Michelle Lavery

Unfortunately, no. It’s going to be an ongoing conversation for a long time, I think.

What is animal welfare science?

Luca / Fin

Well, it’s maybe a good segue into what we want to be talking about this episode, which is animal emotions and animal pain. So I was wondering if we could maybe start by framing how those two topics are distinct from other terms that I often hear, which are animal weights and sentience.

Michelle Lavery

One thing to note as distinct is that you can kind of think of them as two separate like correction factors almost. If you’re maybe making a calculation of like the overall intervention you’re looking at or the overall thing you want to prioritize or your cause or whatever. So you might look at a certain intervention and want to know What does the science of animal emotion tell me about how much of a welfare improvement this intervention will give to each animal? And then the next correction factor you might want to apply is, and how much moral weight do those animals carry in the grand scheme of things? And so I think that the kind of science of animal emotion, animal welfare science really gets at that first piece of like, what does this intervention do for the animal? How does this improve things for them? What’s their baseline starting point? And what would this intervention kind of? give them versus, so the moral weights is much more kind of like weighing this against other causes, how much will this be worse in terms of moral concern?

How is animal welfare science useful for policy?

Luca / Fin

So it sounds like animal welfare science is a little more complex than just trying to, you know, understand pain, duration and intensity and that’s it. And if that’s right, then I was wondering when that more complex understanding is actually useful. Once we already have a good idea of just when an animal really dislikes being treated in a particular way.

Michelle Lavery

Mm hmm. Yeah, I think it’s one thing to understand how much it intensely dislikes how it’s being raised. And it’s another thing to understand what it would rather have. And so that that kind of is where I feel like animal welfare science plays a role for sure is understanding kind of the scientific investigation of like, well, what does the animal actually want versus what does it want to run away from? Which are both things that it can address. But. I think you can’t just understand that it dislikes something. You need something else for it to have, or you need to be a complete abolitionist. And that’s a slightly different way of thinking than what someone would use animal welfare science for. And so I think that’s one way. Another way is that you can’t, you can’t kind of just assume that an animal doesn’t like something or does like something. I think there does need to be kind of a systematic investigation into whether your assumptions are actually correct. So as just a really kind of simplified example, fish can often exhibit freezing behavior when they’re faced with something quite scary. And if you just assumed that, like a human, if you’re exposed to something scary, you try and escape from it, you would assume that zero reaction from a fish means it’s not scary and the fish is not suffering at all. Whereas if you scientifically interrogated that assumption and used multiple other potential correlates of fear, which I’m sure we’ll get into, but if you looked at heart rate, if you looked at other things that were reasonably associated with the experience of fear, you might see that. Interestingly, the fish is freezing, but also having all of these other fear correlates happen. And so then you might say, okay, my assumption about a lack of reaction is probably not accurate. And so I should reassess the situation. And I think there’s lots of cases where that can potentially happen when you’re interacting with species that are so different from humans and can’t speak to you. So I think you do need to take a systematic approach. And that’s where I think the kind of science comes in beyond just intent. We know it intensely dislikes something or wants to run away from it. Yeah.

Luca / Fin

You touched on there as well about how animal emotions and the science around it might intersect with the policy process you mentioned, right? There being a dynamic here with like abolitionism versus incremental reform. I’m wondering, and I’m sure we’ll get into this in more detail later on in the interview, but maybe to give a taste of that. Yeah, like what its role in the policy process here is.

Michelle Lavery

So I think there is an important intersection in the sense that you want whatever policy you’re pushing for or however an industry is regulated to actually result in an improvement in animal welfare, if that’s its goal. And you want to know that that improvement in animal welfare is actually replicable and rigorously discovered. And so for that, you want to make sure that you have a pretty solid scientific evidence base on which to base whatever policy change you’re going to make or whatever new threshold you’re going to set for whatever procedure is being regulated. And I think that’s how they really intersect is knowing that the improvement in the policy that you’re making will actually result in an improvement in animal welfare is what the science of animal welfare that that policy would be based on can give you.

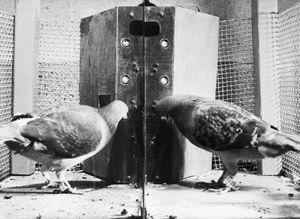

A ‘Skinner box’ style experiment

Mapping emotions

Luca / Fin

So, I guess philosophers like arguing about what counts as an emotion, and I noticed when I tried to reach for a way to define emotions, my mind just goes to, you know, listing examples of human emotions, which is obviously too narrow in this context. So I was wondering if there is anything like an agreed upon understanding of what you’re talking about when you talk about emotions in animal welfare science?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think this is something that a lot of people who are adjacent to the discipline often struggle with. And I think when we’re building scientific collaborations, we spend a significant amount of time kind of explaining this so that we can kind of have a common language with other scientists in other disciplines. So when we talk about an emotion, and the thing to remember, I think, is that… Scientists love definitions of things and they love using words in slightly different ways than normal parlance and also different ways than other disciplines. But within animal welfare science, usually an emotion has kind of component parts. And the part that you might label as an emotion is usually the subjective feeling. So the kind of conscious experience of having an emotion. But there’s also several other kind of components that often accompany that subjective feeling. So there could be a physiological response like a heart rate increase or a cortisol release through the bloodstream. something like that, you could have some kind of facial expression change, or body language could change, posture could change. And so you kind of get these, we often call them correlates of emotion, because a lot of people think of emotion as the subjective feeling, and then all of these other things as associated experiences. But many people think of the entire collective as the emotion at any given time. And then in terms of what you actually think of as an emotion and how you might assess things, there’s a couple different concepts that you can use. There’s kind of the modular way of thinking of emotions, which is where you label them. So things like joy, sadness, fear, anger, that kind of stuff, which is a very human way of kind of putting labels on emotions and thinking of them as distinct experiences. But there is also what we call kind of the dimensional approach, which is where you can almost imagine two axes, right? You have your x-axis and your y-axis. And along the x-axis, you can put valence, so the goodness or badness of a given feeling. And on the y-axis, we call it the arousal or the excitement or the kind of activation axis. And that’s basically just how, if it causes your heart rate to rise, how high does it rise? How intense is the emotion? How much is this kind of causing some kind of arousal or activation in the animal or the human? So if you think of those two axes and you want to plot anger, let’s say, like a really intense rage. you would probably put that in the upper left. So you would have maybe negative valence, high activation. If you were to plot clinical depression, for example, you might put that in the lower left. You would have bad valence, but very low activation. And similarly, you might have like excitement or anticipation in your upper right, but then you might have contentment or like just general satisfaction in the lower right quadrant. And so that I really like as a concept of emotion, and that’s the one I’ve kind of adopted in my scientific work. Because I find it can cross barriers that otherwise would require language. So even within kind of human to human comparisons, if you speak a different language, sometimes different cultures that have developed those languages will decide that different experiences deserve labels. than maybe people in other cultures. So for example, there’s words in Japanese that don’t translate to English that describe very specific emotions. Similarly, there’s words in Arabic that do the same thing. And so you can imagine going to animals, you would have potentially even greater differences in terms of the types of emotions that would deserve words versus not. And this kind of dimensional approach gives you a little bit more of a common scale to put things on. Now there’s pros and cons to everything that you do in science, and there’s always nuance. Nothing is simple. And one of the downsides of the dimensional approach is that depending on the intensity and valence of certain experiences, they might actually overlap when in reality they feel very distinct. So fear and anger, depending on their intensity and valence. could plot exactly on top of each other. When in reality, my reaction to anger is to charge forward and my reaction to fear is to run very fast away. And so I think like there is nuance to be had in that approach as well. And that’s why sometimes modular definitions can be useful to use in conjunction with this dimensional approach.

Luca / Fin

I’m curious about this two-dimensional approach. So I guess you have arousal and valence, and you’re not saying that emotions can be identified with only two factors, but they’re clearly two important ones. But I just noticed in my own case, I feel like I can think of emotions where I actually feel confused about where I’d place them, especially on the valence scale. Like, it actually just seems ambiguous to me. and they’re watching a scary film or something. Is that good or bad? And so I was curious how you think, what methods you use to figure out how to place emotions on those scales?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think you’re getting an interesting question of kind of like having overlapping emotional experiences and feeling them as one experience. And I think it is really hard to unpick psychologically. I think this is one area that animal welfare science hasn’t maybe yet made it to. So. You can imagine human psychology is a little bit farther down the line than animal psychology or the study of animal emotions. But I think that it’s a really interesting kind of question, and I think it gets at how complex your emotional experience can be at any given time. And so kind of even circling back a little bit to the moral weights question, if people are familiar with the rethink priorities work, They kind of looked at as, as kind of their theory for moral concern or how they were going to get to estimates. The underlying idea was that the complexity of your emotional experience could affect how much suffering you could take on at any given time. So for example, if you could have multiple emotions at once, or if you can understand the concept of time or understand that this was going to be unending suffering, those different cognitive capacities that increase the complexity of your experience of the world might cause you to deserve more moral concern than something that has a much simpler experience of the world. And I think your question kind of gets at that is like, I don’t know if we have a good grip on whether animals have straightforward views of the world or experiences of the world or whether they’re incredibly complex, but it’s definitely an area that people have started to think about. I think we need a lot more. work on it before we fully understand what’s going on, but it’s definitely a conversation that’s being had.

An experiment from Harlow (1958)

Consciousness

Luca / Fin

Yeah, that’s interesting. I guess, kind of separating out here intensity and complexity of emotions. If I’m like thinking about this, I could imagine that homesickness is kind of a complex emotion to have because you need to have the concept of a home and then a concept of sadness and the relation between that. But at least as you framed it with the idea of dimensions, nothing in that like. a

Michelle Lavery

The underlying assumption, I think, to all of this is that to to experience an emotion in its fullness with that subjective feeling, you do require consciousness. So you require sentience, which is, as I define it, the valenced phenomenal consciousness portion, which is like a little bit in the weeds, but we can get to that if you would like to get that. But I think So to have a subjective feeling, you have to be conscious, but then there are shades of sentience. There’s shades of consciousness. Like you can have much more complex consciousness. And I think that’s where we haven’t necessarily unpicked everything. We haven’t figured out what’s going on there. And I think that’s one of the benefits of the Moral Weight Project from Rethink Priorities is they really kind of brought that to the forefront as a question. Does more complex consciousness mean that you have a greater capacity to suffer? Or is that in fact not true? And I think the dimensional concept of emotion is very kind of superficial in the sense that it kind of gets at moment to moment emotional experiences, not necessarily these long lasting states like grief, for example, which requires you to understand that your loved one is never coming back. And I think those types of experiences start to also add potentially multiple more axes like duration, like theory of mind, like social cognition. And I think that’s starting to get quite complicated. But I think as a starting point for just understanding, like, what is bad right now, the dimensional approach can be quite useful, at least for understanding organisms that can’t respond to you with language. Yeah.

When is anthropomorphising useful?

Luca / Fin

So, one obvious thing I might do to try to figure out what an animal is feeling is just to observe its behaviour and then compare that behaviour to human behaviour and draw some inference based on what humans are normally feeling when they behave that way. And in that way I guess I’m literally anthropomorphising those animals. I guess I want to know, when am I allowed to do that? When is it appropriate to anthropomorphise?

Michelle Lavery

That’s an excellent question. I call it problematic and unproblematic, anthropomorphism. But I think I’m just going to back up a little bit and kind of maybe give a little context on why anthropomorphism sometimes sounds like a dirty word. So I think back in the early to mid 20th century, especially in psychology, there was this massive push for objectivity. We were like, we don’t want any human emotion words to be applied to animals at all. It’s completely inappropriate. And this was kind of dogmatically pushed on all students at the time. And that has trickled through to like your regular old biology undergrad now. will still receive that little touch of that messaging in their undergrad class in animal behavior. And so you get a lot of scientists who are very unwilling to apply any human concepts in terms of emotion, or even psychology to some, for some people, to animals. And so you’ll get a lot of things like, oh, it’s a fear-like state, the fish is exhibiting fear-like behavior or anxiety-like behavior. And that’s where that kind of like, add on of the like comes from, if you see that in scientific literature. It’s an aversion to putting human words on things. And I think there are a lot of cases where it’s just inappropriate to say the fish looks happy. Like, that doesn’t make any sense. There’s no scientific backing to, like, the fish looking happy. It could just have an upturned mouth. Who knows? Whereas I think there’s some situations where literally all we have is a human concept to go off of. So for something like understanding and sentience even. The only understanding that we have of consciousness in humans is what other people tell us their experiences and what we know of our own. And we’re often going on trust when it’s human self-report. We’re just trusting that the other person is indeed conscious and feeding us real information. And so through various scientific experiments, tests we’ve run in human psychology, we’ve gotten some traits, some cognitive abilities that seem like they’re linked to conscious experience of the world and the ability to do that. And from there, We’ve designed experiments in animals that try and get at the same concept and try and understand whether animals are capable of the same thing humans are capable and require consciousness for. And that’s kind of where the science of animal sentience is kind of using useful anthropomorphism to make these analogies from humans in terms of their cognitive capabilities and what those might speak to in terms of conscious experience.

Luca / Fin

I guess one kind of silly observation is that it does feel legitimate. to look at. But that just wouldn’t make any strategic sense for him. Like, he’d just be failing to communicate that he’s angry to anyone else, and often it’s useful to communicate that. And anyway, so I feel like maybe that shows that inferring emotions based on behavior comparisons plus some supporting story is legitimate, at least sometimes. And so, why not extend that to non-human animals, which share a large amount in common with us? Maybe that makes sense.

Michelle Lavery

I think the other thing to keep in mind is evolutionary history here. So we have evolved as a social species to understand and communicate via facial expressions, via specific body language. And we’re very, very good at it because our entire survival has basically relied on our ability to socially cooperate. And so I think The closer an animal is to us in the evolutionary tree, and the closer its life history is to us, so the more social and the more ape it is, maybe the more legitimate it is to apply your kind of just run-of-the-mill anthropomorphism to it. Whereas when you get to kind of a solitary carnivore, I just think the evolutionary history is not sufficient to support the analogy. And then take it even farther, something that lives in a completely different medium underwater. has a nervous system that has eight brains instead of one, multiple sucker arms, and eyes that evolved separately from our own, but to the same end. It just seems like we’re just too far away for reasonable analogy at that point, unless you’re looking at very specific analogies with very specific support for them. And so in that case, I started getting pretty skeptical of like happy looking octopi. So.

Luca / Fin

Yeah, yeah. I guess there are all these examples of even people who raised some animal for many years, even primates, who just catastrophically misinterpreted the animal’s behaviour, often I guess with pretty dire consequences.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, absolutely. And I think that that comes from misreading evolutionary cues in history. So a lot of primates are genetically quite close to us. But in terms of social evolution are completely different signals are completely different. Social structures are different. And that that can often cause that kind of misreading to happen is just the the history and the way that they have evolved to act and to interact with each other is just different enough from humans that the analogy falls apart.

Luca / Fin

One more potentially stupid thing I kind of want to note here is, so if you take dogs as an example, it totally seems like they can reliably, accurately tell how humans are feeling, at least their owners, in ways that we can just verify, right? And sure, maybe that’s because they’ve been selected to be especially good at that through breeding. Maybe some of that’s through reinforcement, as a particular dog learns and humans give it feedback. But I guess it shows that at least some kind of interspecies empathy or sensitivity is possible in principle, right?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think there’s a lot of examples of interspecies cooperation. Not necessarily, I don’t know you can classify it as empathy or not. It’s not necessarily my area of expertise, but there’s definitely interspecies cooperation. There’s also a phenomenon called social buffering, which is somewhat related. So it’s especially studied in lab rodents. And it’s basically where they’ll have a cage mate, a company, a mouse or a rat that’s receiving a medical procedure, like a surgery or something, something stressful. And the presence of a non-stressed cage mate will cause the stress reaction in the treated individual to be significantly lower than it would be if it was alone. So yet another kind of potential, oftentimes people will call it like emotional contagion, where it’s this like non-stressed individual is keeping the stress reaction low, or similarly, there will be one incredibly stressed or injured individual in a herd or a shoal, and everyone will become scared. And so I think if you define empathy in a certain way and you operationalize it in a certain way, that could potentially be evidence in support of it. Your dog example is a good one. I think my skeptical reaction is that we’ve bred them to be very good at reading us. And so that’s not necessarily a natural ability. That might be something that they’ve developed out of like a domestication survival kind of situation.

Luca / Fin

Yeah, I guess if it’s super artificial, then we can’t really generalize from it.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, it could be, but it’s not necessarily not an example of interspecies empathy. It’s just that it might not have just naturally evolved on its own.

Evolutionary explanations for emotions and behaviour

Luca / Fin

Yeah, maybe you’re thinking a bit more about evolutionary reasoning and how we can use it to better understand animals in a farmed animal welfare context. Can you maybe give some examples?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, sure. Yeah, so as it’s must be obvious to everyone. Farmed animals came from somewhere. We domesticated them from wild animals. So chickens, for example, are bred from wild jungle fowl, which are native to the African continent. And I think one thing that’s quite interesting is an example of kind of a sustained evolved drive for a specific behavior that now no longer really serves a purpose in captivity is dust bathing. So chickens and red junglefowl, wild junglefowl, have this incredible urge to roll around in dust. They are highly motivated to do it. They’ll give up food to do it, they’ll push weighted doors to do it, they just, they really want a dust bath in their environment. And there’s a bunch of hypothesized reasons as to why they want to dust bathe. There’s ideas about it keeping parasite loads low, keeping feathers clean, that kind of thing. And if you think about those hypotheses, a lot of them to do with health are now dealt with in captivity. There’s very low parasite loads in Western poultry farms, at least. Chickens are regularly vaccinated against diseases. Their environments are not necessarily clean, but they’re not dirty to the point of like, being absolutely covered head to toe in mud from walking through a swamp or something. And so those hypotheses kind of break down as like a reason for the behavior. And so what we now understand dust bathing to be is this highly motivated, very important behavior that evolved in red jungle fowl that we haven’t bred out of the animals. It’s very ingrained. It’s very innate as a desire, as a behavior that needs to be performed. It’s something we often call like a behavioral need. And that’s something that captivity has not kind of just made go away, if you know what I mean. And there are lots of these kinds of evolved behaviors that especially species that are less domesticated, like fish, for example, are much closer to their wild ancestors than chickens or cows or pigs. These kinds of evolved behaviors and evolved needs are still quite prescient for those animals, even if we think captivity has dealt with the reason why they would occur. they might still need to perform it because it’s so ingrained and so deep-rooted, if that makes sense.

Luca / Fin

Yeah, and then I’m curious how to draw out the next step. So I can imagine, look, we can observe that these chickens have this evolved behaviour to want to dust bathe. But then I’m curious about, well, how can we know if it gets to dust bathe, was it neutral before and now it’s really happy, or is it in a state of agony or sadness when it doesn’t get to dustbath. I’m not using those as categories, but your dimensional diagram, which is maybe harder to convey in podcast form.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I mean, I can talk about some of the techniques we would use to assess how much of a need that is, and how much welfare it might improve, that kind of thing. So there’s a couple of different ways. The most basic is kind of just what we call preference testing, which is give them two pens, one has a dustbath in it, where do they spend the most time? Now this has pros and cons. It’s easy to do, but dust bathing might only take like three minutes of their day. So they may just be wandering randomly between the two pens when they’re not dust bathing. So a better way would be maybe to run a motivation test or what some people might call a revealed preference test or something like that, where you ask the chicken, how much do you want the dust bath? So will you squeeze through a really narrow gap to get it? Will you give up food for it? Will you push on an increasingly heavy door to get at it? Will you… when given a longer and longer runway, will you run faster and faster towards your dust bath when you want to dust bath? Dust bathe, sorry. And I think those get at kind of how valuable the dust bath is to the animal. When you’re thinking about what baseline versus post-dust bathing welfare might look like, you could literally do like a baseline measurement of several welfare indicators that you’re reasonably certain are useful. So something like, perhaps, I don’t know, comb temperature has sometimes been used as an indicator of stress in chickens. You could look at feather quality as a proxy for kind of like, how healthy their skin underneath is or something. I’m not a poultry expert, but there’s lots of different poultry welfare indicators you could measure at a baseline and then measure afterwards. I think a more interesting approach, personally, would be how does their chronic welfare improve when they’re given regular access to a dust bath? And that’s where you could look at things like… I’m When you’re clinically depressed, you will perceive a neutral facial expression as threatening. So I could give you a completely straight face and you’d say I was scowling at you. And basically scientists have taken this kind of chronic mood altering appraisal phenomenon and applied it to animals. So the idea is that you could train animals on two very different stimuli. So maybe a red light and a white light or something like that, or a black disc and a white disc. And you could train them that one of those stimuli, say the white one, predicts some kind of food reward or something. And the other stimulus, let’s say a black disc, predicts some kind of scary thing, like a puff of air or an electric shock or something. And then basically you could give the chicken regular access to a dust bath for months, let’s say. And you could have tested them at the beginning of that and tested them at the end of it by giving them a bunch of neutral gray stimulus discs. So something that is neither white nor black, something perfectly in the middle. And if they act like they’re expecting food, then you could call them optimistic because they’re thinking that something ambiguous is going to get them something good. If they act like they’re going to get an air puff or an electric shock, you could say the chickens are pessimistic. They’re thinking that something completely neutral will give them a punishment. And in that way, you can kind of get at what the likely chronic mood state of the chicken is. So you could see, well, at the beginning, the chicken was neither optimistic nor pessimistic. It didn’t act at all when the grade desk was presented. Or it was pessimistic because it was a production chicken and it’s probably sad. But then with regular access to a dust bath, you could run the test again. And I would personally hypothesize, given what I know about dust bathing, that the chicken would act more optimistic post regular access to a dust bath because chronic welfare state would likely have improved.

Luca / Fin

That’s extremely cool. That kind of…

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, it’s very complicated. Like it’s a lot… it’s a multi-step process. But… These kinds of tests are really kind of at the forefront of animal welfare science. And I think this is like the really useful thing for getting at lifetime welfare or chronic mood state or how some alterations to an environment can affect like long term mood rather than just moment to moment emotion.

Luca / Fin

Just tangentially, I remember one of my teachers at uni was involved in research on drugs and treatments for depression. and she mentioned that if you wanted to test the effect of, say, an antidepressant on rodents There’s some kind of swimming test to see which ones are depressed. Does that ring a bell?

Michelle Lavery

Oh yeah, forced swim test. Yeah, so the forced swim test is interesting. I am not personally super in support of it, but I see where it comes from. So it comes from another concept that we observe in clinically depressed patients, which is called learned helplessness. So it’s this kind of just like… Why even bother? I’ve already learned that nothing I do makes a difference. And so the idea of the forced swim test is, it is literally, it’s dropping rodents in water. Usually the water is body temperature, so at least it’s not cold. And essentially, treating them with different drugs or keeping control groups untreated, and seeing how long it takes for them to give up swimming. So how rapid the learned helplessness occurs, basically. And so the idea being that a good antidepressant will keep it from happening for much longer than, let’s say, a manipulation that causes depression in rodents or mimics depression in rodents. And so that’s that test is used, kind of hijacking the human phenomenon of learned helplessness and using kind of a model of it to test different interventions.

Luca / Fin

that will then be used again on humans.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think there’s probably quite a few. None are coming immediately to mind, but I do know that from the kind of biomedical world, a lot of tools for understanding how different drugs work on humans or human diseases can be very useful for the people investigating the welfare of those animals used to test the interventions. So for example, I had a lab mate who actually did… the world’s most interesting PhD project. Basically, lab rodents are typically caged in the… essentially a small plastic shoebox with very minimal substrate, food, maybe some nesting material, depending on the country. I think Europe is better than North America, but I’m not entirely certain of that. And then you can also give them big enriched cages with hammocks and ramps and things. And there’s lots of evidence to support that they really are motivated to get those things, to interact with them. They want them in their environment. And so you can reasonably assume that the welfare of the rodents in enriched cages is probably better than the ones in barren cages. And there’s also lots of evidence to suggest that like stress relevant disease outcomes are worse for the rodents in standard cages versus enriched ones. And so this lab mate of mine actually tried to diagnose clinical depression in standard housed lab rodents, using a lot of the tools that human depression research uses to test antidepressants. And so essentially what she did was take the DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing clinical depression in humans and tried to find analogous tests in rodents. for the world. the things we use to test antidepressants essentially, to try and then diagnose the test subjects themselves with clinical depression. And so it was really, really interesting. I think ultimately she did not diagnose them with clinical depression, but she diagnosed them with something along the lines of dysphoria, which is like a gentler version of clinical depression, but still diagnosable, which is pretty wild. But that’s kind of an interesting example of where you can use what Biomed has developed.

Luca / Fin

to the world. in order to get a sense of how animals behave when they’re depressed. And then that might include behaviours which we don’t normally associate with depression in humans. Um, yeah, cool. Yeah, one question I had here was, you know, when people talk about farmed animal welfare, there are just some very obvious harms from, say, physical pain or really acute stress. But I wonder if there are also signs of really significant harms in the form of… I guess a wider array of psychological issues. So say depression or fear or something else?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think that’s very scientifically plausible. Whether we will have useful and tractable interventions for dealing with those psychological disorders is where I think a lot of the questions for me come up. So for example, with a painful procedure, causes acute pain and acute stress. That is something where I could see several tractable interventions potentially being useful. So for example, the EU requires sedation and painkillers during surgical castration for boars. They require anesthetic or painkillers for beak trimming in chickens, and on and on, disbudding for cows, that kind of thing. And that’s something where you can write that easily into policy, well, easily being debatable, but you can write that into policy. That can be a requirement and the dose can be very obviously written out in a guide, and a veterinarian can easily sign off on it. And ultimately, your big question there is, can they afford to buy the painkillers? Whereas treating something like depression in a farm animal, while I agree that it could potentially be over the longer term, far more impactful on welfare than an acute pain from a beak trim, let’s say, I think it’s harder for me to think of things that we have on hand right now that are ready to go. that could actually influence that in a farmed setting, other than banning cages for layer hens, banning gestation crates for pigs, and pushing for slower growing broiler breeds, which those are three major things we’re already pushing for. And so I think there are things we’re already pushing for for other reasons that could address these, but in terms of actually treating animals with Prozac, for example. is scientifically, technically possible, like you could do it. But I just don’t see how it would be tractable from both a public perception and economic point of view.

Case studies for reform

Luca / Fin

Yeah, well, maybe sticking then with things that are tractable in the near-term horizon, or perhaps had already occurred. I’m curious if you can give an example or walk us through one of the stories of where studies like these, so looking into animal emotions and animal pain, have been important and critical for reforming and incrementally improving the lives of farmed animals.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, there’s a couple. So a really old one, I guess, is I was talking about really simple preference tests earlier. So just literally giving like two pens, one has a dust bath. So one issue that was addressed a while ago was ammonia concentrations in barns. So chickens produce nitrogenous waste. It releases ammonia into the air, and ammonia is not pleasant. It causes eye irritation and tracheal and esophageal irritation in humans. It can cause. reading problems if you’re exposed to it for long enough in high enough concentrations. And so you can assume, given the physiology of chickens, like in their trachea is not that different from humans, like we’re not talking about different chemistry here. Ammonia is probably also irritating them. And so basically, what was done was a series of preference tests, essentially, where they gave a couple different compartments to chickens. And they held those compartments at different ammonia concentrations. And they just looked at where the chickens prefer to go. And rather unsurprisingly, to be honest, the chickens by far preferred to spend a lot more time in the compartment with the lowest ammonia concentration they were offered. And so essentially, these studies were kind of like underpinning an assumption that was probably reasonable to make in the first place. But. They were cited in policy where thresholds for ammonia concentrations were set. And so there was, again, some pushback from industry in the sense. So it’s not like we’re taking the science at face value and just writing it into a policy. There’s always like a give and take because to lower the ammonia concentration, industry has to install air purification systems or better ventilation systems. And that comes at a cost. So ammonia concentrations are not exactly where the science says they should be, but they’re definitely lower than they used to be because that science demonstrates. better for the chickens.

Luca / Fin

Right. So should I imagine that animal advocacy groups are the ones who are funding or doing these studies themselves to then take to policymakers? Or should I imagine that policymakers are reforming this law or this regulation and are then looking towards science to fund themselves to help arbitrate this dispute?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, this is an interesting kind of ecosystem of funding and scientists and scientific groups freedom and government needs and policy. So backing up quite a bit, the discipline of animal welfare science, which is essentially the study of animal emotion, was kind of prompted by, in the 1960s, the publication of the Bramble Report in the UK, which was essentially, factory farming is getting really big and really important, and we have not considered the lives of the animals in the factory farms. We should probably do that. And the UK government said, Wow, thanks, Bramble. That’s yeah, we probably should. And at the same time, Bruce Harrison was publishing Animal Machines, which was this kind of like very, like, emotive, very obvious, kind of diatribe against factory farming. And I think I love Ruth Harrison, but essentially there was public outcry. The government was receiving an official report and all of a sudden there was a little bit of research money released. So they started with a few targeted studies to specific scientists, and then slowly this kind of built momentum into small clusters of people who were calling them, calling themselves animal welfare scientists in the UK. And then slowly that spread and spread until you get these little clusters of animal welfare scientists in North America. So there’s one in Guelph in Canada. There’s one at UBC. There’s several in the United States at UC Davis, Michigan State, et cetera. There’s one in Edinburgh. There’s a bunch through Europe. There’s one in Nigeria now, which is amazing. And these little clusters develop kind of more and more scientific techniques for looking at things more and more kind of and build out the field. They write textbooks, they train students, they disseminate knowledge, they start conferences, they start research societies, etc. So that’s kind of the general trajectory over time. And largely a lot of this was funded by just like. run-of-the-mill government research grants. So a lot of countries will have just grants for science. It’s not necessarily science for a purpose, it’s just grants for scientific research. And so a lot of these researchers were getting basic research grants to work on these very applied topics, to be honest, which is an interesting kind of push and pull with the government funders. Then you would also get targeted research projects from governments wanting to reform policy in response to public outcry. So you’d get things like targeted projects on what kind of floor does a layer hen want in her cage, stuff like that. Then you would also get industry responding to public outcry. potentially wanting a welfare element to some of their production grants. So they might give a grant to a consortium of scientists or a single scientist to look at how can we reduce stress so that disease resistance and meat quality goes up? Oh, and also you can do your silly little emotion experiment too. And so a lot of these researchers were kind of piggledy-piggledy cobbling together almost a research program on animal welfare. by getting funding from a variety of different sources, not very much of which was from the advocacy movement, because I think most advocates would probably support me on this. There’s not a lot of money to go around in the farm animal welfare advocacy movement. And so a lot of these researchers, I think, have a lot of respect for them, honestly, most of them, because they are kind of, driving this body of evidence that might be in contrast to industry incentives, but often they’re kind of sneaking them into industry funded grants. Sneaking might be like an overly suspicious sounding word, but it was like these scientists were so curious inherently about animal emotions. And some of them were also motivated by like the ethical considerations that they were facing as well. But they were shoehorning these things into these grants where it was actually quite difficult to get these these experiments done. Yet they were still forcing them through alongside this like meat quality project or this like, better slaughter for the human technician project, or something like that, where they were like, well, this project is going on anyway, I can collect welfare data while it’s happening and do this other cool thing on the side. And that’s a lot of where the body of evidence that we currently have comes from is basic research and these kind of like, sneaky little projects.

What incentives do animal welfare scientists face?

Luca / Fin

This sounds like a real. mix of funding sources and motivations and backgrounds. Could you say a bit more about what kinds of incentives that produces? If you’re a PI on some potential research project, what kind of pressures are you feeling and in what directions?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, yeah. I think you have rightly identified the heterogeneity of this field. So I think sometimes starting from kind of the beginning of where your incentives would come from, it can depend on what your background is. So if you are a biomedical researcher, you might be quite incentivized to publish in really high-powered journals like Nature. And so you might want really pithy projects. You might be really incentivized to do like the breaking ground stuff. And that might mean that you need a lot of funding from a big government grant, or you might need a lot of funding from industry. And if you are a pure animal welfare scientist born and bred in one of these little research clusters, you might be really motivated by just like the pure desire to investigate animal emotion. And that might mean one of your few places is a basic research grant from the government, or you might be doing these production grants and shoehorning your emotion experiments into the side of them. If you’re funded by industry, if you’re at a publicly funded institution, or like an established university, you are largely protected from your funders’ desires. So oftentimes grant agreements with universities will include clauses that ensure scientific freedom. If you’re tenured, the reason tenure exists is so that you can speak out without being fired, for example. And similarly, there’s a lot of mechanisms kind of in the university structure to separate funder from scientist. Because scientific integrity and objectivity is is one of the core tenets, right? However, you have to, you have to understand that, like, if you want a sustained source of funding, there is a degree to which your funder has to be satisfied with your work. So either you’d be quite upfront with them at the beginning. and say, listen, I’m going to do good science, and I’m going to work on things that you care about, and things that I care about. You may not like what I have to say, but if we can come to an understanding, we can continue this relationship. Or if you’re maybe a slightly younger person, slightly less strong willed person, slightly less good at communicating, it might, it might end up in a not great situation where you feel like you have to kind of sustain a relationship. I think that is much harder to actually identify in practice, because I think it can be quite subtle when it happens. I don’t think it’s an outright like, well, now I have to sell out to industry, and now my decision’s made. But I also don’t think anyone quite ever gives up their desire to do it. to build a lab. affecting the quality of your science that you’re doing for industry, maybe it just makes it really hard for you to branch out and do the really radical animal emotion research, or support your colleagues in doing that, or publicly call for it, for example. And I think that’s one of the pushes and pulls. The other thing is obviously, like I mentioned, with the kind of person with a biomedical background, everybody, everybody in science needs publications to sustain themselves. That is like the currency of the field. And I think that can sometimes get in the way as well, where instead of doing maybe the big, hard projects that might not pan out in a publishable result, you might need to do smaller things, especially at the beginning of your career, smaller, less impactful things quicker to get your publication record to a place where you have the freedom to maybe take bigger risks in your experiments that might not pan out with anything useful.

How does animal welfare science interact with animal advocacy?

Luca / Fin

Yeah, interesting. So we’ve talked about, I guess, the relationship to academia, government, and industry. I’m curious if you can speak at all to the relationship of animal welfare science and animal advocacy in particular.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, this is one that I’ve kind of interacted with a little bit now in my role as Open Phil, because I interact with a lot more advocates than I used to. And I have so much respect for what they do. I’ve had a few interesting interactions where, I mean, I’ve just, there’s a perception amongst some pieces of the movement that animal welfare scientists is, animal welfare science, is kind of apologizing for industry or facilitating industry. And I think there’s validity to that statement. Like there’s definitely some animal welfare research that has maybe just painted industry in a better light than it should have been. However, I think there is also reason to believe that a multi pronged approach to this problem is useful. So if you, unless you are an absolute 100% hardcore abolitionist, there are animals suffering right now that need to have better lives. And a lot of the roots to a better life for those animals suffering right now are through evidence-based policy. And I think that’s where animal welfare science can play a really important role for advocates wanting to push for things like that. Thank you. And I think also, moving forward, there’s potential for science to also demonstrate that like, alternatives exist. So maybe instead of farming a certain breed of chicken, we should farm a different one. We should farm slower growing broiler breeds, and we can produce those slower growing broiler breeds, things like that. And so I think there is like, Maybe a perception that animal welfare scientists can be industry apologists, but I think that would discount a lot of the work that animal welfare scientists have quietly been doing with their little government grants and their little shoehorned experiments to build up the body of evidence that we have that supports the corporate campaign asks, the policy asks that we have today. That’s my slightly biased as an animal welfare scientist two cents.

Regulating animal experimentation

Luca / Fin

Amen. Yeah, one thing I was curious about was when we’re talking about animal welfare science or just animal experimentation in general, often this involves inflicting deliberate pain on animals. And, you know, the number of animals involved in experimentation is much smaller than the number of animals which are farmed, but it’s still not a significant number. So I’m kind of just interested in what’s up with animal experimentation. Like, for instance, who are the people who are determining and enforcing where the line is and what kinds of experimentation are allowed or not allowed?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, yeah. So I think there’s a few elements to that question that I’ll kind of address. So in terms of regulation, it depends what type of your facility you’re doing your experiments at. So publicly funded institutions in Canada and the US, which is my area of expertise, I apologize. are overseen by committees that do essentially ethical review on the experiment. Sometimes there’s a centralized body, like in Canada, it’s the Canadian Council for Animal Care, that will set out guidelines for how animals in labs should be treated and what different procedures are what they call it a category of invasiveness. So how painful or how much suffering a given procedure will produce. And you’ll have to write up what you want to do with the animals before they come into the facility. You’ll have to get that approved with the on-campus animal care committee. And then once that’s approved, you will be subject to regular inspection to make sure you’re not working what’s called off protocol. And I think in the US, it’s largely similar. It’s called an IACUC, is your kind of like local oversight body that kind of approves animal use protocols. And I think in In theory, this is a great system. There’s oversight on things. There’s ethical review. In practice, there can be a lot of heterogeneity in the quality of review that things are getting. So you can get some centers with really fabulous animal care committees with people who have really thought deeply about animal ethics and the trade-offs with scientific progress and how statistical and experimental design should play into the use of animals, that kind of stuff, really good, gritty. review is happening. And then you can get some universities with just, they don’t have that capacity. They don’t have a culture of animal research, for example, or they don’t have a culture of kind of these, these people thinking deeply about these thorny issues. And so review can kind of be de facto approved or be kind of like, as long as you’re not doing X, it’s fine. And so I think quality can vary quite a lot. Thank you. And that’s one area I think we could improve is just making that a lot more consistent with maybe a third party College of Animal Experimenters or something. But in terms of the actual kind of animal welfare science experiments that happen, which is kind of an interesting subset of the animal experimentation that happens. I think animal welfare scientists, when they’re thinking about doing the experiments, are often thinking about it in kind of a utilitarian way where you’re thinking about potentially inflicting a lot of pain on your control group and testing out your welfare intervention. And then thinking about how, if I find that this actually does improve welfare, it could affect my health. these massive numbers of farm animals if written into policy at some point in the future. I think that’s often how people in animal welfare science are thinking about their experiments and the need to potentially cause pain. Because I don’t think there is an animal welfare scientist who wants to cause pain. You don’t go into animal welfare science thinking, oh, great, now I get to torture animals. usually it’s the exact opposite. And so oftentimes you get these thoughtful people thinking about this utilitarian case for their experiments. And then as an additional layer, you often get people who are trying to minimize the harm within the experiment. So for example, if you’re running a cognitive experiment like this judgment bias task I was talking about earlier, instead of using an electrical shock as your punisher, you might choose to refine that punishment to an air puff, which causes less pain, but still is useful for training the animal. And similarly, you could also, if it doesn’t affect the design of your experiment and the validity of your outcome, you could choose to keep your animals in enriched environments instead of barren ones. You could choose to give them a dust bath if they wouldn’t otherwise have one. And so there’s certain like… Depending on the nuance of your experiment, there’s certain ways you can kind of refine the actual experiment you’re doing as well to make sure it’s still in line with your personal ethics.

Luca / Fin

Yeah, I’m curious to whatever degree you might be able to comment or like have an insight here, get a better sense of like what the demographics of like animal scientists look like. You mentioned that it’s very heterogeneous, but I’m curious, even in rough guesses or something, if you were to compare how many people are say vegetarian or vegan or some otherwise, you know, public commitment towards combating farmed animals. Yeah, like how scientists here might stack up compared to the general population of the country they’re living in?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think the word that I would pick out there is public because I think there are, from personal relationships in this field, I know that there are a lot of vegetarian and vegan animal welfare scientists. Whether they will publicly say that they are is another question entirely because I think a lot of scientists hold on to their scientific objectivity, their integrity, and their desire to remain neutral. accept in the face of evidence. And so when they’re trying to build a relationship, for example, maybe with industry, so that they can get an interesting welfare project off the ground, it might not be in their best interests to publicly be vegan at that point. Similarly, if they’re trying to present evidence to, let’s say, a parliament committee or something where they’re going to influence policy, it also might be better for that outcome for them not to be public advocates. Because there is kind of the privilege of appearing objective and the seriousness with which you get taken that way. However, I also think that the majority of animal welfare scientists, if you give them, like if you ask them on an evidence based question, what they agree with versus what they would advocate for, I think most of them would advocate based on the evidence. And so I think you get a lot of scientists who will kind of like privately make ethical choices about their diet and publicly make open, strong statements based on evidence about animal welfare. And I think that’s probably given the constraints within which scientists must conduct themselves for scientific ethics purposes. I think that’s probably. a pretty reasonable kind of situation to find yourself in.

Who should consider doing animal welfare science?

Luca / Fin

One thing I was meaning to ask is, if I imagine someone who’s got excited about doing useful work on farmed animal welfare, and let’s say they’re relatively young, and they’re considering what kind of career path to go down, and they might consider advocacy, and maybe that’s policy, maybe that’s more meaningful, and maybe that’s a career path. you know, public facing stuff. I guess I’d be surprised if they really thought of doing animal welfare science as a serious option. So I wonder if you think it often should be an option for such people and if so, what kinds of people are a good fit for that kind of work?

Michelle Lavery

Like I said before, I think you have to be swayed by the utilitarian case. Otherwise, I think it might be very mentally painful. I think Definitely people should take farm animal welfare science seriously as a potential career path. However, I will caution that science moves very slowly. So for impact to come from the work that you do will take at least probably a decade, because to be honest, you don’t want a policy change based on one paper, you want a policy change based on a critical mass of replication. And so I think that if you are looking for, like, if you are primarily motivated by rapid welfare improvements for farm animals, I think that farmed animal welfare science, like the actual research element of it, might be difficult to swallow as a career path because it does take many years, it takes a lot of money, it is a big investment, and it also takes a long time to see return on that investment, if that’s your primary motivation. However, If you are already a trained scientist, and you are primarily motivated by scientific inquiry and curiosity, yet also have a passion for farm animal welfare and advocacy, I think I would love to see you take a piece of your career and make it about animal welfare science and apply whatever skills you have scientifically to these really tough questions that we’re trying to handle. Because the more people with expertise working on this, I think the better. However, I think I would just caution a young person who is potentially highly idealistic and wanting to really see big changes. I don’t think you would get that from farmed animal welfare science. unless you were like 30 people at once, and then you all just kind of swamped the show. Unfortunately, if I’m speaking directly to one person, though, you are only one person still. You are not 30 digital minds. So just slow your roll.

Luca / Fin

I guess I’m curious then, so for the scientist who is thinking about transitioning or putting part of their career into this field, You mentioned that this is often a very utilitarian calculation, and it feels especially important to really consider whether the expected benefits here might be worth the cost that you would incur. When viewing this through the ultimate goal of influencing policy or improving animal welfare down the line, what are the types of questions and the types of policy windows to look out for or to kind of imagine of how this might pay out?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think that’s a great question. So I think… you’re kind of getting maybe a lot of scientists often focus primarily and rightfully so on the science and publish their work. And then that’s kind of where it ends. And I really love when scientists think a little bit farther down the line, and I would love to help them think farther down the line. And I think there are also lots of advocacy organizations that would like to kind of pull them a little farther down the path to impact as it were. And so I would really encourage interaction like Compassion in World Farming, Eurogroup for Animals. Lately, they’ve been really good about thinking about how gaps in evidence are influencing what they can and can’t push for, policy-wise. I think scientific engagement with those types of advocacy groups is really great for the scientists’ understanding of what they should tackle. There are also a few people out there writing work about research gaps. So not to toot my own horn, but I have a paper out there about research gaps that are relevant for Canadian aquaculture policy. There’s a couple of people who have written stuff about what we still need to find out about poultry welfare. and how we can feed that into corporate campaign pushes and policy pushes. In terms of actual policy windows, I think that is very kind of variable. Lately, we had a potential opportunity in the EU. They were overhauling a lot of legislation or planning to. We are now a lot more uncertain about whether that will move forward and what shape it will take, because we’ve had a couple of disappointing updates. head of the EU Commission. But that was a big policy window that potentially was going to be a big opportunity for science to make it into legislation. We do still have a bunch of EFSA, so that’s the European Food and Safety Authority, opinions coming up about fish. It would be great, regardless of whether legislation is going forward or not right now, to have those stacked with really good evidence for fish welfare. And so anyone who’s working on fish right now, I would really encourage you to think about adopting some sea bream into your research program. Because we don’t know a ton about sea bream and sea bass welfare, and EFSA is going to write an opinion on them in mere years from now. But yeah, I think keeping your ear to the ground in terms of the news in particular is really useful. And then interacting with the more policy-minded advocacy organisations can also be great. And I can almost guarantee you the advocates will be really excited to talk to you.

Open questions

Luca / Fin

Yeah. Yeah. Speaking of research gaps, I guess, C-BREAM aside, are there any especially big gaps just across the board that you think people should really prioritise? Or is it a bit more particular and ad hoc and piecemeal than that?

Michelle Lavery

Um… Yeah, I think there’s one that seems to be coming up for a lot of our species, and that’s stocking density. So that’s just how many animals are packed into a given unit of space in a system. So we talk a lot about it in aviary systems for layer hens, which are what are now predominantly replacing the cage systems as we get away from cages. In broiler systems, we talk a lot about stocking density. And in fish as well, stocking density is a big kind of area of concern for welfare. And I would say in fish, we know the least about it and how it interacts with welfare. But understanding what a good stocking density looks like in a welfare lens is probably like a big gap that we have. roughly across the board, but predominantly for fish. And the reason stocking density can be really important for welfare is because it can affect a couple different things. So it can, it can both If your stocking density is too low, it can cause anxiety, especially for animals that have evolved to take safety in numbers approaches to anti-predation. And then if it’s too high, you can get territorial behavior that causes aggression. You can literally just get animals stepping on each other or just bumping into each other. And you can also get like waste. and it can be this kind of like multifactorial issue. If you interact with farmed animal welfare at all, you will hear that term in almost every species you talk about.

Luca / Fin

One thing I’m also curious about is the future of animal welfare science. things that come to mind for me. Maybe AI could potentially be very useful. Maybe brain imaging is getting especially good. Yeah, wondering if there are any advancements that you’re excited about on that front.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I think, so two suggestions. I think brain imaging has been really interesting in understanding brains that are very different from ours. So, for example, fish have a very different way of kind of developing from just the little embryo tube that we all start as. The brain actually folds outwards rather than kind of folding in on itself, which means that different parts of that tube that end up as the brain end up in very different places than a mammalian brain. So they don’t, for example, have a hippocampus. They don’t have like frontal lobes as such. And so we don’t know where, which parts of the brain light up or interact or do different things to control different abilities, different experiences, that kind of thing. And so that’s been brain imaging, different techniques for brain imaging, both alive and not alive, have been really useful for kind of detangling that kind of stuff. AI, I am not, I’m not a to be honest, well-versed enough in AI to understand how it might interact with the study of animal sentience, necessarily. But I can definitely tell you… that people are using it to monitor welfare on farms. So there’s lots of algorithms and kind of programs being thought up for particularly picking out lame animals. So looking at kind of like biomechanical markers and then looking at differences in how those track and then identifying, for example, lame cattle that need to be pulled out and treated or lame chickens that potentially need to be killed. human eyes would not detect until much later in the progression of lameness. And so I think that’s potentially a tool that could be useful for catching welfare problems earlier, especially ones that are visible like on a camera observation kind of situation. […]

Luca / Fin

Yeah, I can totally imagine that, you know, in the actual policy or like regulatory space, these are going to be very difficult conversations. I can imagine it really triggers a lot of people’s instincts of this being, you know, anti nature, and like what have you that I guess it just really goes to reemphasize the point that at least being able to have credible scientific evidence about how much pain goes into or comes out of, you know, the cutting beaks or burning horns and stuff is going to be a really important point.

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, and don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying these are like immediately trafficable preventions here. I think it would be a slog to try and convince the public that this was acceptable. But I do think that in kind of a very long-looking view towards animal welfare, this is potentially a technology to watch for sure.

How can advocates best use animal welfare science?

Luca / Fin

So I guess we’ve been talking a good amount about… potential steps and potential actions from researchers themselves. I’m curious if you can perhaps briefly also speak to what policymakers or people advocating on behalf of animals should be thinking about, and in particular how they might be able to better use animal welfare science to help improve their welfare.

Michelle Lavery

There’s a couple of things. It’s a complicated field. And it takes a lot of training to understand the nuance of even just a tiny slice of it. And so I completely understand if it seems overwhelming to even delve into what it is. any of the science behind animal welfare pushes and asks. That being said, I think engaging with scientists occasionally, like take one for coffee, ask one for a Zoom date. And you will probably get a very excited person on the other end of the call who will explain things. in much more human terms than what they wrote in their paper. I would also say there’s a lot of great research seminars online. Like a lot of us have just like posted talks from virtual conferences in the pandemic just on YouTube for free, which is another way where you could get a slightly more palatable taste of animal welfare science than reading kind of the dry literature. I would say that I would encourage a basic understanding of how things get understood in animal welfare science, so the different kinds of experimental paradigms, the different assumptions that things are based on, especially in your particular area of advocacy or policy, because I do think that the quote unquote other side. Whether that’s industry, whether that’s the public, whoever, like, the science can also be twisted and used for their benefit as well. And it’s good to know if it is indeed being twisted in an unethical, unfair, unjustified, non rigorous way, or if it indeed does support them. And it’s also useful to know the quality of the evidence you’re using, because if it’s bad, it’s very easy for you to be attacked on that basis and have your argument completely knocked to smithereens. And so I think like. Understanding at least the superficial kind of like key take home points on the quality of evidence for both sides of the issue you’re looking at is really useful for you understanding like where you might have to shore things up. If that makes sense. Yeah, yeah. The other pro tip I’d like to just throw in is the scientific publication paywall is real. And I understand that it can be a real hindrance for NGOs and cash strapped charity workers. And so I really do want to encourage the use of the corresponding author. So usually the author list of a scientific publication will have one person with their email address listed. Just email them for the PDF of the paper. Just do it.

Closing questions

Luca / Fin

That’s a great suggestion. I guess that like segues us nicely though, to asking what are some good resources to learn more about this stuff? Especially say if you’re not a scientist and you’re looking to get a better understanding of the field. Are there perhaps three resources that you could recommend to listeners who might want to learn more about everything we’ve talked about here?

Michelle Lavery

Yeah, I have kind of a random selection, if that’s okay. Totally. There’s a really good, if you want like a quick, a quick thing, there’s a really good science news article called How Do We Know What Emotions Animals Feel? It quotes some of the best welfare scientists on the market right now. And I think it gives a good overview of kind of just generally some of the techniques I’ve touched on here and some of the other ones that are floating around. So I would recommend that article for like a quick, quick recap. Then I would also, as much as it may be slightly broken right now, there are a lot of welfare scientists on Twitter or whatever it’s called now. There’s both animal welfare scientists and animal welfare philosophers, who are also quite interesting to interact with. Both of the Canadian animal welfare research centres have Twitter accounts. The Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare and UBC’s Animal Welfare Programme. There’s also scientists like Beth Ventura, Carly Moody, Jeremy Marchant, and Iathare Oluwaseyan. who’s from Nigeria and is great, Maria Roervang, Joao Saraiva, who’s like the fish welfare guy. And then there’s philosophers like Jonathan Birch, Heather Browning, Adam Shriver, Kristen Andrews, and also himself, Peter Singer. They’re all on Twitter and they post great resources, they post interesting takes, they’ll do threads every once in a while, they’ll post talks they’ve given at conferences, and so that’s a great way to kind of just like see what they’re up to and see what they’re talking about and get kind of quick explanations and access to other resources. And then if you really want more technical detail on the actual, like, experimental design behind some of this in a pretty digestible way, there’s a short, small, reasonably sized textbook. It’s not a textbook. It’s a small book by Marian Dawkins. It’s called The Science of Animal Welfare, Understanding What Animals Want. And I find her style of writing is quite easy to follow. It’s not this kind of dry, technical, scientific stuff. It’s mostly just clear explanations of how you would get at different questions.

Luca / Fin

Nice. And yeah, maybe one thing I’ll add in the mix as well, which feel free to endorse or strike, is the Welfare Footprint Project, which I learned through you, but I actually found to be on the more technical side, but still very engaging. And it’s got some great infographics,

Michelle Lavery

which I always love. They are great. Yeah. Yeah, I love their tools. You can kind of change different parameters and get different estimates for different things. And I find that really useful for understanding how different parameters that they’re kind of using interact with each other and change. So yeah, the interactive element of that is great.

Luca / Fin

Yeah, and I’ll also like quickly add that one thing that really stuck with me from that resource specifically is really like charting through the whole process that like animals like, have to go through in the farming process and really trying to quantify the pain at each step of that, I think, yeah, is a different way of looking at it. But like,

Michelle Lavery